By RICK DUNHAM

Co-Director, Global Business Journalism Program

I was at home during Tsinghua University’s winter break when news of the coronavirus outbreak made its way into Chinese and international media in January.

As soon as I read about the deadly epidemic, I knew that my life, and my students’ lives, would be significantly disrupted. Little did I know that it also would turn into an opportunity for me and my Tsinghua School of Journalism and Communication colleagues to experiment with innovative distance-learning tools, offering our students the chance to continue their education in new and exciting ways.

Despite some initial optimism in Chinese media, it was clear that the epidemic that started in Wuhan was out of control. With 35 years of experience as a journalist in the United States, I had experience in separating facts from rumors, and calmly carrying on in times of upheaval and panic. As international co-director of the Global Business Journalism program, a prestigious English language masters program at Tsinghua University, I immediately focused on my students.

Half of our Global Business Journalism students are Chinese, and they were home with their families. Our international students live in more than 20 countries around the world. Our office found out where they were and how they were doing. (They were all healthy and surprisingly calm.) Most were home with their families overseas, though a few students remained in China during the winter break, either on campus or with relatives in China.

My next priority was to prevent panic while honestly sharing the facts available to GBJ’s leaders. I realized it was important for our program’s global website, GlobalBusinessJournalism.com, to provide reliable, timely, accurate information about the coronavirus and its impact on Tsinghua students.

Early optimism, fueled by upbeat coverage in some Chinese media, led some people in our GBJ community to believe that spring semester classes would resume on campus with minor delays. As someone who has coped with emergencies as a reporter and manager, I strongly believed that there was more than a 90 percent likelihood that we would not be able to return to Beijing any time soon.

Well, unfortunately, I was right. Chinese government officials instituted quarantines around the country, and intercity travel was severely restricted. Almost every other country canceled all flights to and from China. Our students, even if they wanted to, could not return to Beijing.

Out of necessity came opportunity. Through conversations on Skype and WeChat, my colleagues and I discussed ways to create virtual classes so we could resume classes as scheduled on Feb. 17 and give students a valuable educational experience. The university’s visionary leadership had the same idea, and aggressively pursued solutions.

Tsinghua tried to create a proprietary online learning platform, but the beta tests showed that it wasn’t ready for widespread use. We needed to find a stable, reliable platform for online classes.

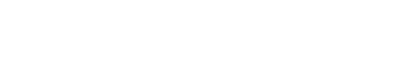

We also had a logistical problem. Global Business Journalism students are spread out over 22 time zones. It was almost impossible to find a time that would work for everyone. For my advanced news writing class, we settled on 8 a.m. in Washington, which is 2 p.m. for my students in France and Spain, 3 p.m. in South Africa, 5 p.m. in Oman, 9 p.m. in China, and 10 p.m. in Japan and Korea. Thank goodness Global Business Journalism students are flexible and adventurous.

Then came the Iowa caucuses in the United States on Feb. 3. As odd as it sounds, the massive technology failure in Iowa played a key role in our Chinese academic experience. The Iowa Democratic Party didn’t properly beta test its new app, and the result was disaster. It was a PR disaster, but, more importantly, it was a failure that did not serve their customers: Iowa voters, the media and the American public.

I realized it was vitally important to carefully test platforms in advance so we could provide a positive experience for the students. Our international journalism staffer, Li Chengzhang, and my teaching assistant, Wan Zhixin, tried a few and concluded that a conference app called “Zoom” was our best prospect. The university and Zoom’s Chinese subsidiary reached an agreement to let students use the platform for free until June. We beta tested the app repeatedly: once with just four of us, then a “dry run” with the entire first-year Global Business Journalism class. Then we were ready for classes, or so we thought.

Of course, there were a few glitches caused mostly by the varying qualities of internet connections around the world. But our class was an educational triumph. Students could see me, hear me, see my PowerPoint presentations, and see articles that I had called up on my computer screen for analysis. All of the other Global Business Journalism program’s classes proceeded without incident, and the student reaction was overwhelmingly favorable.

“Even though the virus has resulted in the [journalism] school having to use a virtual classroom, it’s still brought so many good stories to the front page,” said Hai Lin (Helen) Wang, a GBJ master’s student from Canada who has been staying with her grandparents in Tianjin. “I hope we can all take advantage of this time.”

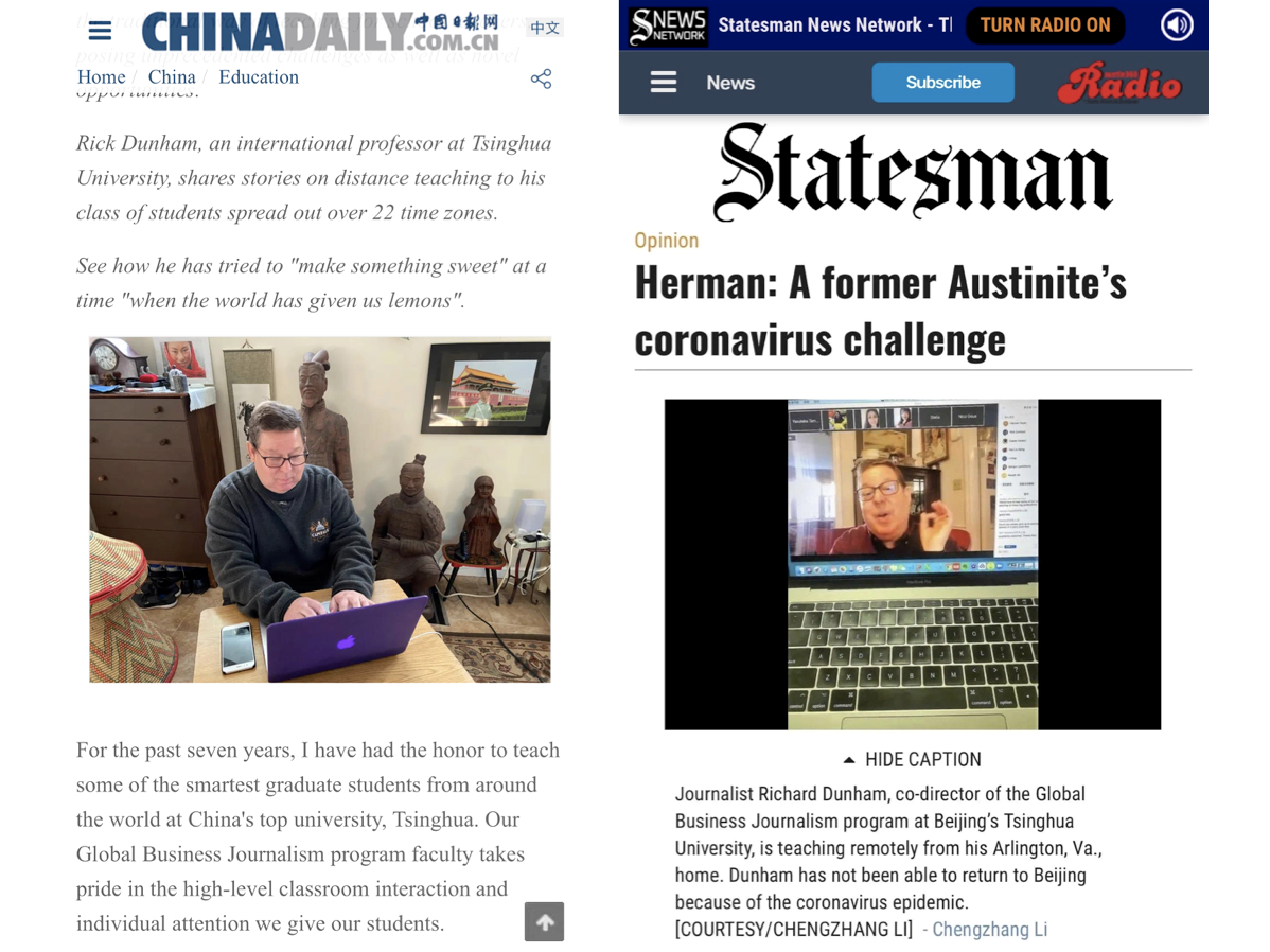

I conducted the first class from my dining room table in Arlington, Virginia. For the second class, I created a China-themed classroom in my basement, with two life-sized terracotta warriors from Xi’an in the background.

I feel heartened by the outpouring of support from around the world. A typical message came from said Ralph Martin, an emeritus professor of computer science at Cardiff University in Wales and a former guest professor at Tsinghua. “I hope your online courses go well and things will soon be back to normal,” he wrote in a note shared on university social media accounts.

I’m taking this one week at a time. We could have a technological meltdown any week. But I am cautiously optimistic. And I am looking for the silver linings in this dark cloud. For one thing, I can now ask prominent journalists, academics or policymakers in Washington, Europe or Africa to join our class in real time.

I have great sympathy for everyone who has gotten sick, and mourn those who have died in the coronavirus epidemic. I feel a sense of empathy for the billion-plus people whose lives have been upended. While my academic routine has changed significantly, I can’t say that I have suffered, like so many of my friends and students in China. I think of them (and talk to them) every day.

In good times and in these challenging times, Tsinghua University has inspired me to become a better person and a better teacher. As a professor who loves teaching the brightest aspiring journalists from around the world, I owe it to my students to give them an educational experience that they will always remember … in a good way.

The world gave us lemons, and we are trying to make something sweet out of it. As one of my Texas friends said to me: “Lemonade, Rick. Lemonade.”